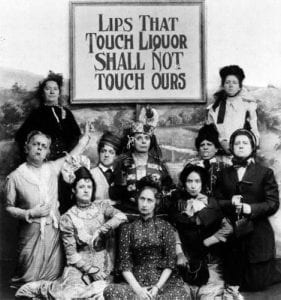

For the American alcohol tradition, the end came in the form of an unlikely alliance of social progressivism and religious conservatism. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, in conjunction with the Anti-Saloon League, led the charge against the legal sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages, and were instrumental in the passing of the 18th Amendment in 1920. What resulted was a story that most of us have heard before.

consumption of alcoholic beverages, and were instrumental in the passing of the 18th Amendment in 1920. What resulted was a story that most of us have heard before.

Prohibition led to mass poisoning from consuming industrial alcohol that had been poisoned by the government to deter consumption, or from types of liquor improperly distilled. Simultaneously, it criminalized an industry that had once been a vibrant part of society. It obliterated the small-batch beer industry and spawned America’s first home-grown organized crime syndicates, while setting the stage for the alcohol monopolies that still dominate the industry to this day. Ultimately, in 13 years, the 18th Amendment was repealed by the 21st, but not before the suffocating constraints of Prohibition radically warped American culture forever.

For cannabis, things went quite a bit differently. It wasn’t social progressivism or religious devotion that inspired its prohibition, though anti-cannabis agents would claim to be motivated by both. In reality, cannabis was not the cause of many social ills at the time, nor was it even being used by a large number of Americans in a recreational context. By 1900, the practice of regularly smoking cannabis for recreation was relatively limited to immigrant populations in the American Southwest, a fact that proponents of Prohibition would twist to their own purposes.

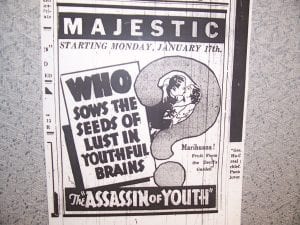

By 1915, newspaper stories ran all up and down the California coastline connecting recreational cannabis use with rape, assault, and delinquency, especially in immigrant and migrant populations. The stories were sensational and dramatic, and painted a very clear picture of cannabis as corrupting to the morals and corrosive to the soul, and capable of inducing a murderous, rapacious lust. Of course, the printing of these stories had nothing whatsoever to do with cannabis inspiring crime in any group of people, and everything to do with the cost of printing newspapers.

At the turn of the 20th century, a national conversation was taking place in the textile and paper industries, centered around the potential use of hemp as a substitute for timber in the manufacture of paper. Hemp is superior in almost every way to wood pulp as a base for paper, being cheap, durable, and extremely sustainable. The industrial application of a relatively new machine called a decorticator had very recently made it possible to consider using hemp instead of wood pulp on a mass scale, by automating the process of stripping the fiber from the plant. Previously, harvesting hemp fiber involved a process called “retting”, where hemp would be left to rot in the sun until the fibers could be stripped from the stalk by hand. The decorticator eliminated the waiting period and preserved much more of the original material, and its advent threatened to revolutionize paper-making forever.

At the time, a newspaper baron named William Randolph Hearst controlled much of the press in the American Southwest. One of the wealthiest people ever to live, Hearst truly valued the economic advantages of vertical integration. Hearst not only owned all the newspapers, he also owned all the printing hardware, and most importantly, the timber forests used to generate pulp for newsprint. Being able to pipeline the resources needed directly to his presses saved him spectacular amounts of money, which he employed to build movie theaters, menageries, and heated indoor swimming pools on his estate, the last of which he literally paved with gold.

Obviously Hearst, as well as other major economic world players embroiled with timber interests, such as the du Pont family and Andrew Mellon, felt threatened by this possibility, and collectively, they began to explore their options for preserving their wealth. Unfortunately for them, while timber was huge in America, it wasn’t the whole industry that was threatened, but more specifically the subsector of the industry devoted to paper processing. Hearst in particular stood to lose in a way that no other single agent in America did, and because he couldn’t stop the technology by attacking it as such, he decided to attack the plant it would depend on.

Ultimately these “titans of industry” would bring their collective political and economic resources to bear on cannabis at the most fundamental level, hoping that prohibiting the growth of the plant for psychoactive purposes would stifle its potential as an industrial resource as well. Hearst leveraged the influence that his social positioning gave him, and was one of the first people to deliberately use news publication to influence public opinion on a mass scale for his own profit. This “yellow journalism”, as it came to be called, was a series of techniques that Hearst used to taint public opinion of not just cannabis, but many different domains of life, most notably running article after article extolling Cuban virtue and demonizing the Spanish, to fan the flames of conflict that would become the Spanish-American war. The immigrant populations he worked so hard to connect to violent crime by way of marijuana were victims of racism leveraged for economic gain.

Ultimately, between the vast influence of Hearst and men like him, the willing complicity of Harry J. Anslinger, our nation’s first drug czar, was easily obtained. Despite feeling that cannabis was not a threat to the fabric of American society, four years into his tenure he changed his tune dramatically, waging a nationwide campaign against the plant. Perhaps the looming threat of Bureau of Narcotics budget cuts as the Depression wore on spurred this shift. Maybe it was the pressure exerted by Hearst and the timber lobbies, or the simple realization that their interest turned cannabis into a potential political blue chip.

Regardless of his reasons, Anslinger abruptly ramped up his campaign aggressively, playing into exactly the same kind of racist stereotyping that Hearst had been invoking. In fact, the very word “marijuana” is a joint effort between Hearst and Anslinger used to connect cannabis to immigrant populations. The only medical professional present at the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, a representative of the American Medical Association, strongly criticized their use of the term even at the time, indicating that it was basically a smokescreen to keep the people of the time from understanding that there was even a connection between hemp and the plant being targeted. Many people who had reason to oppose the Act were unaware of its existence, and Anslinger’s campaign was very, very successful.

And so things begin to become a little more clear. The stigma associated with alcohol use built gradually over time, and culminated in its Prohibition, after the end of which a more and more robust and tolerant culture has developed. In the case of cannabis, the stigma was manufactured for economic purposes, and engendered in America with the beginning of its Prohibition, meaning that rather than being at the center of a controversy from the outset, cannabis faced almost universal condemnation because of the slander it had endured. Furthermore, by the time this stigma was created, alcohol Prohibition had already ended, and alcohol culture had already begun to heal.

There’s an obvious cultural stigma associated with Prohibition, and that stigma gains power and cultural cachet with each passing day that Prohibition remains in place. Alcohol was only prohibited for 13 years, and the alcohol industry in America was forever changed and warped. Cannabis prohibition has endured for well over half a century, and its culture was so fledgling to begin with that it has been relegated to the margins of society in a way that far outpaces the stigma of alcohol.

If this was the beginning of the difference in the way the two are perceived, that’s an understandable thing. Figuring out how, and why, cannabis prohibition was so much more enduring than alcohol prohibition deserves a closer look. Next time, in our final segment, we’ll talk about the cannabis black market and modern regulated economics, and where they work to keep each other alive.

<a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/51035655711@N01/”>Foxtongue</a> via <a href=”http://foter.com/”>Foter.com</a> / <a href=”http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/”>CC BY-NC-SA</a>

<a href=”https://www.flickr.com/photos/tinfoilraccoon/15851498/”>Rochelle, just rochelle</a> via <a href=”http://foter.com/”>Foter.com</a> / <a href=”http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/”>CC BY</a>